- Pages: 290

- Genre: Children's Books, 5-8 years, 9-12 years, 13+ years, Illustrated

- Year: 2015

- Translation: Sample translation in English available

- Book size: 15.3 x 23 cm

- Sold to:

- Faroe Islands (Föroya lærarafelag)

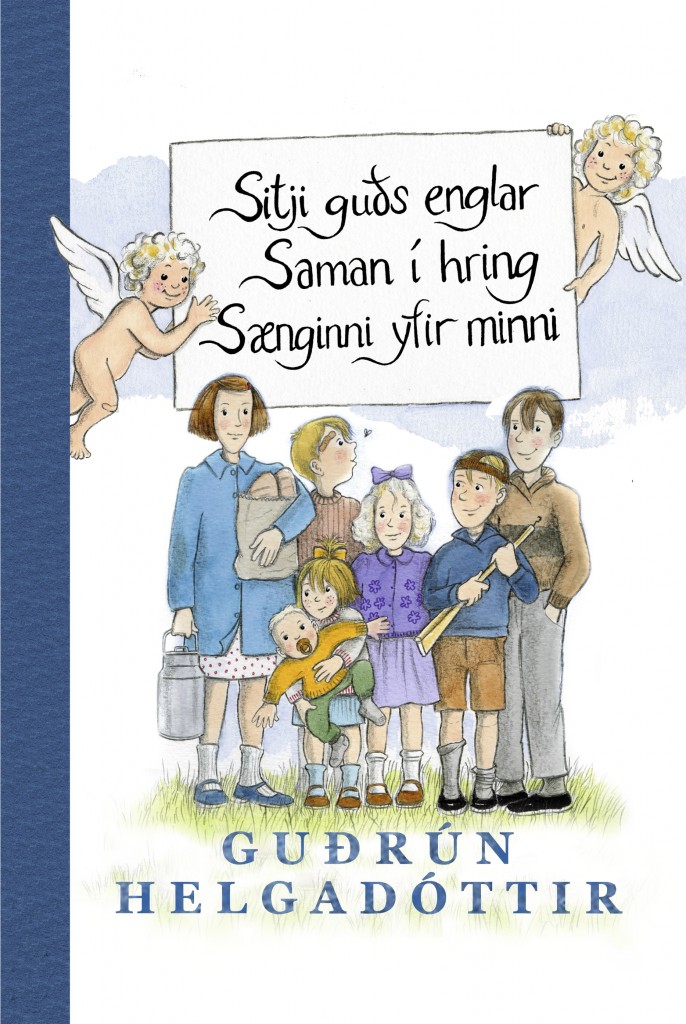

May Angels Watch Me Through the Night Wake Me in the Morning Light (2015)

Author: Gudrun HelgadottirIn a tiny house in a tiny village lives a large family: a sailor and his wife, seven playful children, their god-fearinggrandmother, and their foulmouthed grandfather. There’s a war going on in the outside world and it’s not long until the conflict stretches itself all the way to Iceland — with good and bad consequences.

Gudrun Helgadottir’s trilogy about this colourful family has enjoyed immense popularity since the first installment was originally published. Here all of the stories have been collected into one splendid collection.

Review by Silja Adalsteinsdottir, in Tímarit Máls og menningar, literary journal, 3/84 :

The latest book by Guðrún Helgadóttir, May Angels Watch Me, is set in a small town in the middle of the second World War. The actual events of the story take place from autumn until just after Christmas, but the tranquillity of this sleepy little town has been abruptly disturbed some time before the story begins. The nuns no longer live in the monastery above the town, because the American forces have taken it over, making their mark on town life much more definitively than the nuns ever did.

The reader primarily makes the acquaintance of the family living at number 2 of an unnamed street, consisting of grandmother and grandfather, father, mother and six children, who become seven during the course of the book. A colourful family this is. The father and mother have not yet made a home of their own, despite having all of these children, or perhaps in part because of this. The father is the sole breadwinner for the extended family. Since he is only a deck hand on a fishing vessel, who likes to take a drop too many when he is ashore, his family is not exactly rolling in it. Grandfather had an accident as a dock worker, losing his sight almost completely and destroying his legs. He can do little to make himself useful, while practically everything has to be done for him, even to the point of emptying his chamber pot downstairs, a job which most often falls to Heiða. Grandfather finds an outlet for his thwarted energy in language which makes grandmother shudder.

As might be expected, it’s no easy task to be the oldest of such a brood, and 11-year-old Heiða finds it a tall order. Heiða feels sorry for her grandfather, but is also ashamed of him. She is not especially fond of her grandmother, but has nonetheless adopted her ethical stance and fears of what others will think. She loves her mother, of whom she sees steadily less and less, making her all the more intolerant towards her brothers and sisters, whom she is also fond of, despite everything. Hardest of all for her is to put up with her father, who breaks all the rules and who can be blamed for practically everything which goes wrong: their poverty (grandmother says that their mother should have married someone working ashore, with a better income), his waste of money on candy and liquor when he does come ashore, which Heiða feels makes him a laughing stock (the worst of all), and her mother’s recurrent pregnancies.

Everything is different at number 12, Kristín’s house. Her husband, Steingrímur, works in an office; they have plenty of money and everything in their home is clean and tasteful. Everything there fits Heiða to a tee, and she is every inch the daughter they long to own: clever, hard-working and ambitious. And it’s there she gets to stay when her mother is admitted to hospital after giving birth and the youngsters have to be sent hither and thither to be looked after. Everything goes smoothly for Heiða until Christmas arrives and she opens the present from her father – a toy telephone. Now everyone in this fine household can see what a silly fool her father is. He does not even know how old she is! She tries to explain things, making up a story once more as so often before to make her family look better, to lift them up to her own level, but fails.

As a character, Heiða is extremely well drawn. She is every inch the disciplined and self-confident child she wants to be. She succeeds in everything for which she alone is responsible and for a long time she believes she can control her life on her own. She is concerned about her appearance, but intends to make up for it by becoming famous and remarkable. The eldest sibling’s stifling feeling of responsibility appears in her dreams, but during her waking hours she is determined and confident. She feels herself to be perfect and shows no tolerance towards others who are not.

Contrasts

Both the character portrayal and social fabric of the story are based on contrasts right from the beginning, between grandfather’s loving gruffness and grandmother’s cold civility, as well as between the father, on the one hand, and mother and grandmother on the other: splurging as opposed to thrift, spoiling children versus disciplining them. This enables the author to say much in few words; the contrasts reveal each other, not least in the descriptions of the homes where Heiða and Kristín live.

There are a variety of sharp contrasts between the town’s residents and the soldiers: on the one hand, the poor but colourful lives of the town dwellers and, on the other, the well-off but monotone, male military society. Despite considerable interaction between them, the military are intruders; no one knows how they will behave and underneath everyone is a bit uneasy in their presence, even the young boys who are drawn to seek out the soldiers’ company. And against the backdrop of the wartime destruction hymns sung by the soldiers under the walls of the monastery on Christmas Eve are at the same time unearthly and ridiculous. The greatest contrasts, however, as Heiða gradually comes to realise, are between those people who risk their lives continuously at their daily tasks at sea, like her father does, and the others who live comfortably on land, enjoying the fruits of their labour, like Bárður, the vessel owner, who risks nothing and owns “a big house and two Caddies”.

It is Birgir Björn, a young seaman and the son of the couple who live at number 12, who points out to Heiða how unfairly she has judged her father; he really is a hero, even if he hardly knows his own children, and maybe drink is his way of escaping from a life he hardly can deal with. Heiða is confronted by a different set of values than she has been accustomed to, causing a crack to form in her self-assured view of the world. There are more cracks to come. When two local vessels go missing, she suddenly realises that a child like herself has no control over anything. Existence is far from simple and manageable – and she is filled with anguish.

The contrasts in the town before and after the sinking of the vessels are very striking. The narrator clearly and succinctly conveys first the all-pervasive fear and then the sorrow of the residents, just as effectively as their petty quarrels and gossip were portrayed earlier. Equally clear is the maturing of the young girl during those fateful days when life teaches her tolerance of individuals and to see herself in proportion to others.

The story ends as it began, with grandfather putting the flock of children to sleep. Despite the harsh contrasts the story has presented, a secure place exists in this world, one which Heiða has now found.

Method

The story is told in the third person, even though Heiða is the main character, and the narrator, her thoughts and views are always close at hand. She surveys this scene from the past with regret and some bitterness, as she is exposing the myth of uncomplicated childhood. Yet the story is highly entertaining, both in its style and individual details. Perhaps it is just this mixture of loss, pain and humour which gives the story its special character.

Guðrún [Helgadóttir] has very likely availed herself of various memories from her own childhood in this book. But it is not the possible relationship between Guðrún herself and Heiða which makes this a true story, but rather how deep its roots go and how well crafted is the structure built upon it. The social background of the book is gradually expanded and reinforced, all the principal characters are treated with respect as individuals at the same time as they are viewed in the context of their environment.