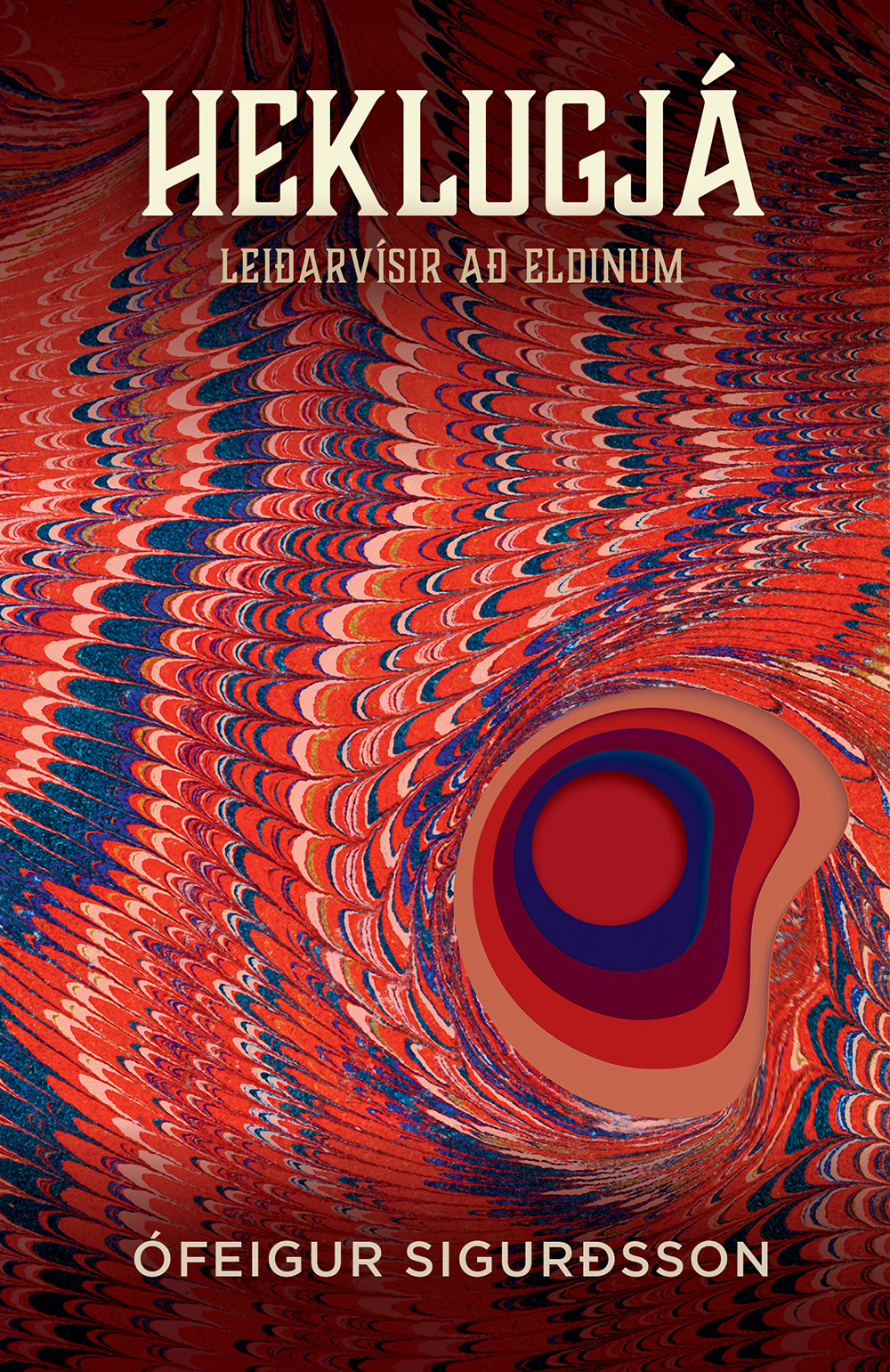

In 1755 Reverend Jon Steingrimsson from Skagafjordur travels south to Myrdalur to look after his wife’s farm. He lies under suspicion of having murdered her former husband and has been expelled from his position at Reynistadur Monastery. The South, however, is not a desirable place in which to dwell: Katla is erupting and Myrdalur is shrouded in a cloud of ash. Jon goes to live in the Badstofuhellir cave along with his brother and a farmhand. In letters to his wife he describes the many things that happen to him that winter. He also reflects in his letters on the story of the love between him and Thorunn, which turned out to be so fateful.

- European Union Prize for Literature 2011

“The style is masterful…an artfully drafted text in a tremendously

well-structured story that mirrors reality both then and now.

Without a doubt one of the best novels of the year.”

FRETTABLADID DAILY

“The long title does not lie: this is truly a novel in which the narrator knows deep down that he is preparing for new times. It is a historical novel about Jón Steingrímsson, the so-called “fire-priest,” when he was young and in love; it is also a novel about an alleged crime, the narrator being the accused and having to deal with the charge. It is about Iceland under a dark cloud of volcanic ash, at a time when a tiny gleam of the Enlightenment reached the country in the guise of men such as Regent Skúli, Eggert Ólafsson and Bjarni Pálsson, who all play a role in this novel, which is, forgive the expression, enlightening about the Enlightenment in Iceland.

This story of Jón is told through his letters to his wife, which is highly appropriate: the epistolary form was quite common in Europe in the late-eighteenth century, and by means of even just this one element Ófeigur Sigurðsson grasps the spirit of expression recognizable in texts from this period. He also captures the style extremely well and presents a credible image of the written language of the period without ever being pretentious or using archaisms that would be strange or unwieldy; because of this, the reader comes much closer to the historical period and characters.

Nor is the time period chosen haphazardly, or it is perhaps on the author’s side: the year is 1755, when the Great Earthquake shook Lisbon to its roots and Katla spewed its most violent eruption over the people of Iceland. The protagonists, the brothers Jón and Þorsteinn Steingrímsson, are in fact located beneath the volcano’s shower of ash, since they and a worker live in a cave in the Reynir District on Iceland’s south coast.

The Enlightenment is perhaps the historical period that we, at least in northern Europe, understand to some degree as the actual start of a new era, with two main trends taking precedence: ideas on mastering nature and secularization. At the same time this entails a paradox, precisely because the latter occurred to some extent due to the overwhelming force of nature. For instance, the Great Earthquake in Lisbon gave Voltaire reason to criticize religion, and especially the idea of the philosopher Leibniz that we live in the best of all possible worlds. This raised the rhetorical question: how could such a thing happen if God exists and we live in this best of worlds?

The paradox is found in the fact that at the same time, people began to apply their powers of knowledge to a greater degree against nature, no less the optimism of the Enlightenment than the promises of religion; knowledge and control of nature thus became the new Eldorado or the promised land of the Enlightenment, in which one not only tends one’s own garden but also clears new lands. Now we most likely face the idea that knowledge and control of nature have led us down an alley in which the revolution will be made by nature and not by men, because it is entirely unfeeling and overcomes all species, including man.

In his story, Jón truly stands at a crossroads, as underlined by many different things: by his scholarly pursuits in the cave where he and his brother are staying, by the visits made by the main messengers of the Enlightenment to Jón in his cave, where he is engaged in translating none other than Leibniz, thus perfecting the irony; the world where he is living seems to be one of the worst possible: Katla is spewing ash over everything and he is to a certain extent a refugee, due to the suspicion of murder laid by all the slanderers in the country upon him. The only thing that gives him reason for optimism is his love for his wife, who will join him the following spring, and the child she is bearing.

This is precisely what makes the story so exceptionally well conceived; the hostile environment cannot overcome the love carried by the letters, sometimes with the help of St. Christopher, apparently; something involving yet another doubling of viewpoints in this neatly composed story.

Another striking aspect of the novel is found in the poetic insertions, in which the style is reduced to staccato lines of verse, so to speak; these are prose passages for the most part, but inserted into them are slashes, as are used to mark lines of poetry within a prose text. To me, these often appear to indicate a different level of consciousness, dreams or actually Jón’s musings, but whether they actually belong to the letters isn’t always easy to tell. The reflections and descriptions can be exceptionally beautiful, as may be seen in the description of the earthquake of 11 September 1755, which without any doubt can be considered one of the most sublime achievements in Icelandic literature this year.

However, it is not only these passages that are a pleasure to read. The entire book, which is so well written, gives us not only an exceptionally good work of fiction to read, but also illuminates the ideas and movements that still set their mark on our lives. At the same time it reminds us of nature, which gives everything and spares nothing.”

GAUTI KRISTMANNSSON, VIDSJA/NATIONAL BROADCASTING SERVICE